Nedim Gürsel, born in 1951, is a Turkish writer. In 1979, he received in

Sorbonne his doctorate in comparative literature after completing his dissertation

on Louis Aragon and Nazim Hikmet. He returned to Turkey but the unrest

there in 1980 persuaded him to go back to France.

In 1976, Gürsel published A Summer without End, a collection of stories. For

that collection, in 1977, Gürsel received Turkey’s highest literary prize, the Prize

of the Turkish Language Academy. After the 1980 Turkish coup d’état, a

military tribunal charged that Gürsel’s collection had slandered the Turkish

army. In 1983, the Turkish military censored Gürsel’s novel The First Woman.

Although the Turkish authorities dismissed the charges against Gürsel, their

actions made A Summer without End and The First Woman unavailable in

Turkey for several years.

In 2008, Gürsel published The Daughters of Allah. The book prompted the

Turkish authorities to charge Gürsel with insulting religion. In June 2009, a

court in Istanbul acquitted Gürsel of the charge.

Gürsel is a founding member of the International Parliament of Writers and of

Academia Balkanica Europeana.

Besides the above mentioned pirze, Gürsel’s awards include the Abdi Ipekçi Prix

for his contribution to the bringing together of Greeks and Turks (1986) the

Freedom Award by French PEN Club (1986), The prize for best international

scenario by Radio France Internationale (1990), Art and Literature Chivalry by

French Government(2004), Prix Méditerranée étranger (2013), etc.

By Nedim Gürsel

Situated in the easternmost part of the Aegean Sea, barely five nautical miles from the shores of Anatolia, Rhodes is the largest of the Dodecanese Islands, and, after Crete, Eğriboz and Mytilene, the largest island in Greece. According to the legend, when the gods divided up the world between themselves, they forgot the god Helios, who was completing his daily circle around the earth. Zeus was outraged by this injustice and sretched out his hand, ripped off a piece of land and gave it to Helios. This magnificent island was named Rhodes. Once changed into a mermaid, she would give Helios seven sons and a daughter. And one of the sons himself would have three sons. The grandchildren of Helios shared the island, founding several towns: Kamiros, Ialysos, with its slopes facing the sea – the Acropolis that is still there today is the spot from which the most beautiful sunsets can be observed, and finally Lindos where, to this day, the sight of the castle of the Knights Hospitaller of the St. John Order remains for all to see.

But if I came to Rhodes, it was not to admire the most beautiful sunsets in the world. When I left Marmaris, I was thinking of Sultan Cem, who, five hundred years ago, on an autumn day as hot as this one, was forced to leave his country forever, arriving in Rhodes not like me, on a fast sea bus ferry, but on a gallion chartered by the Grand Master of the order, Pierre d’Aubusson. This gallion, the great treasure-bearing nave, which carried the heartbroken son of Mehmed the Conqueror, made a stopover in Rhodes. As for me, if I undertook this trip, it was to trace Sultan Cem’s footsteps, when he landed on the island in July, 1482, so that I could tell the story of his tragic destiny, which came to an end with the poison the Borgias poured him. The first part of my trip is Rhodes, which was ruled by the Knights Hospitaller in those days, and where Cem took refuge for a while after being defeated in his fight for succession.

At the time of his death in 1481, Sultan Mehmed, the conqueror of Constantinople, left two heirs: his elder son Beyazid, who was governor of Amasya, and Cem, the younger one, who ruled Konya. Distraught by the sudden death of the sultan, the Grand Vizier Mehmed Pacha sent a messenger to each of the two heirs. The first one to arrive in Istanbul would ascend to the throne and should, according to the rule set by the Conqueror, execute his brother in order to “insure the continuity of the State.” Sinan Pasha, the beylerbey of Anatolia, had the messenger sent to Sultan Cem killed. That was how Beyazid, although he was further away from Istanbul, arrived first and took the throne. Cem, however, did not accept his elder brother as the sultan. He claimed he was entitled to the throne as his brother born when their father was only heir to the throne, while Cem was born during his time as sultan. He assembled an army, went to Bursa and had the Friday sermon read in his favor; but Beyazid proceeded to attack, defeated Cem’s army at Yeni Şehir and forced him to flee. He first saught refuge in Memluk Sultan’s Kayıtbay, but in fear for his safety he contacted the Knights Hospitaller, whom he had met personally during peace talks while his father was alive, and asked for their protection. That would mark the beginning of his 13-year exile, which would last until his death at the age of thirty-five.

Cem was more audacious, more innovative and, at the same time, more impetuous than Beyazid. During his stay in Kayıtbay, he went on the pilgrimage required by Islam and in an ode written in Mecca, he said: “If one cannot be Sultan, may one accept to be a Dervish.” He had, however, a burning desire to rule and, in order to get to the throne, he would go as far as to propose to his brother a division of the Empire. Cem was a poet of great sensitivity. He could be called simultaneously the first Ottoman to go to Europe and the first Turkish poet to die in exile.

The first thing that struck me upon my arrival in Rhodes were the walls of the city. The palace of Grand Master seemed insurmountable, with walls higher than those of a Rennaisance castle, with its towers, its battlements, its strongholds. The walls rising on either side of the castle completely surround the city, from land and sea. Under its flawless sky, Rhodes, a symbol of the two civizations, Christian and Muslim, that flourished in its midst, with its rooftops, its belltowers, its domes and minarets, resembled a jellyfish sprawled out in the sun. The arched doorways, the circular towers supporting the walls, the canons positioned in the ditches with their canonballs the size of millstones all awakened memories of longs sieges, of endless wars, of days of fire and blood. I was fascinated by the narrow streets lined with stone buildings, mysterious inner courtyards and a Gothic architecture rarely seen in the region.

Our ship, leaving behind it the port of Mandraki, which we had entered between the statues of a male and a female deer, passed alongside the windmills. We passed the tower of St. Nicholas, which has protected the two ports since the 15th century and which hindered the Ottoman fleet on two occasions. And we arrived at the trade harbor, where the giant ocean liners cast their anchors.

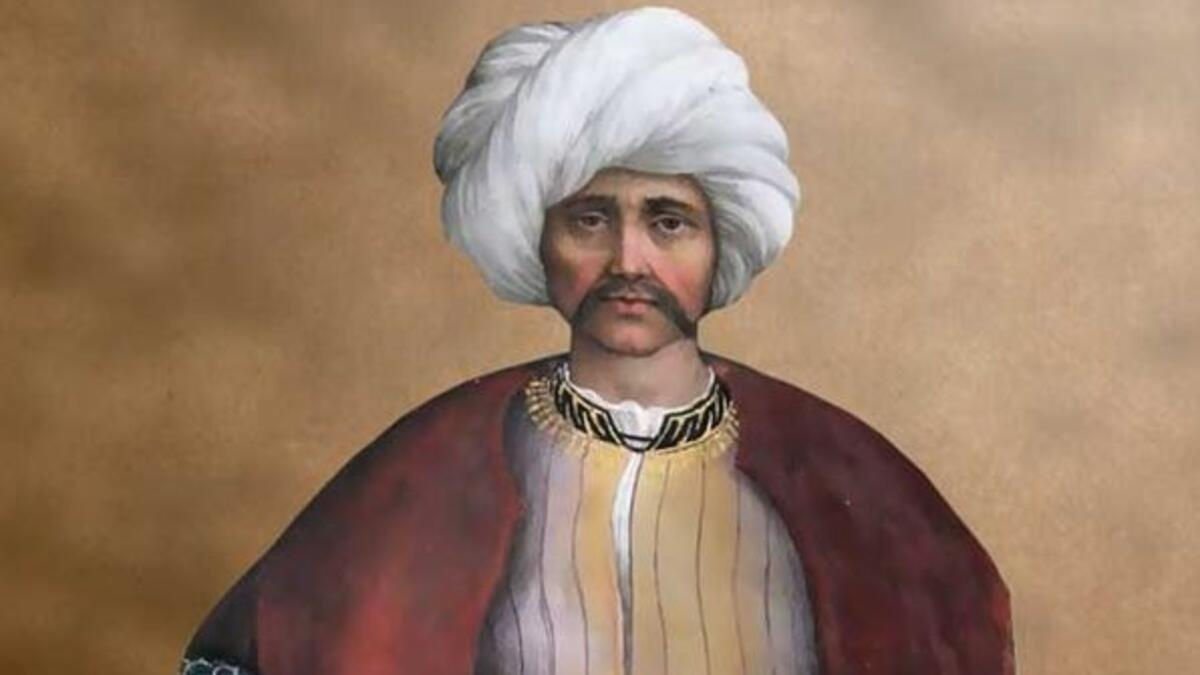

As I entered through the gate framed by tall towers and decorated with the coat of arms of the knights of Jerusalem, the founders of the St. John Order, and a Virgin Mary with an infant Jesus surrounded by St. Paul and St. John the Baptiste, I imagined Sultan Cem entering through that same gate five-hundred years earlier with his procession; I could see him pass on his proud horse, down the streets paved with Maltese stone, welcomed with grand fanfare by the Great Master Pierre d’Aubusson and moving into his residence under the curious stares of the crowd, made up of the Greeks, Latins and Jews who inhabited the island in those days. A direct witness of the event, Caoursin, one of the leading figures of Rhodes – besieged in vain by the Ottomans for the first time in 1481 – wrote that Sultan Cem, whom he had seen up close, was “tall and fair,” slightly cockeyed, bearing a resemblance to his father Mehmed the Conqueror, with his strong hawk nose tilted to the left, his short, sparse brown beard, very elegantly dressed and with “a toubled, yet dreamy air” about him. This is how the French writer Edouard Sablier describes the arrival of Sultan Cem in his documentary novel based on historical sources:

“Upon its arrival in Rhodes, the procession received a grand welcome. A wooden bridge covered in exquisite carpets was drawn from the upper deck of the gallion so the prince could disembark on horseback. The magnificent reins covered in precious stones and the silk garments bearing his coat of arms were carried by his valets. The excited crowd of people gathered in the streets, on balconies and terraces, to see and cheer the son of the Conqueror of Constantinople. (…) The Great Master, his gold-harnessed steed covered in a caparison of gold brocade adorned with gems, awaited in the church square in the midst of civil and military buildings. He was surrounded by noble young horsemen in lavish attire and followed by the wealthiest commanders and the future succession candidates. As he led Cem and his following to one of the most luxurious palaces in town among cheers and canon blasts from the strongholds of the castle, the crowd surged on, all the way to the inn reserved for the accomodation of the French knights.”

It must be noted that this official welcome has been faithfully represented by a drawing illustrating Caoursin’s book, which he, just before his death, gave to Pierre d’Aubusson in 1503, and which is kept today at the Bibliothèque Nationale de France. In this picture, under the word Zizim written in Gothic script (the westerners called Cem ‘Zizim,’ the name given him by his mother, a Hungarian princess, who, upon joining Mehmed’s harem, gave up her name, Sonia, for Çiçek Hatun, or ‘Lady Flower’) we can follow step by step Cem’s stern descent from the gallion with his cortege of Ottomans in turbans, his entrance into the city amid the sounds of trumpets through the vaulted gates flanked by the two towers, greeted, on foot, by the Great Master Pierre d’Aubusson and the knights. The St. John Order (St. John the Baptist, in this case) was established in the 11th century by the merchants of Amalfi in order to accomodate the Christians of the Holy Land during their pilgrimages to Jerusalem. Very soon after, however, they became a military order, forming one of the most powerful establishments in Palestine. In 1291, under pressure from Saladin Eyyub, it was forced out of the region and took refuge in Limasol, Cyprus. The order then moved to Rhodes and, until the fall of the island under the Ottomans in 1522, dominated not only the Dodecanese, but the entire eastern part of the Mediterranean.

The knights of the order came from families of Catholic European nobility. Eager to perpetuate the principles of a feudal society and the tradition of knighthood, they swore to defend Christian values. They constituated, in the southeast of Europe, a military force in opposition to Islam and the Ottoman Empire, which intended to take over the Balkans after the fall of Constantinople. They imagined themselves as the keepers of the Catholic faith and Latin civilization. The order was set up similarly to a state, under the rule of a Great Master elected for life by the nobility and the clergy, and was divided into eight regions according to language: Germany, England, Spain, Castile, Italy, France, Provence and Auvergne.

When Sultan Cem landed in Rhodes in July, 1482, the order was headed by Count Pierre d’Aubusson. The knights gave the contender to the throne an official welcome, but their intentions were to make use of him against Beyazid. They would immediately send ambassadors to Istanbul who negociated an agreement with the sultan and succeeded in extorting from him a yearly allowance of forty-thousand ducats for the upkeep of Cem. The latter had fallen into a trap by seeking refuge with them. He was, in a way, their prisoner, condemned to remain their hostage. Until his death, he would go from one European castle to another, he was received in palaces, but his freedom of movement was limited and his status was almost that of a captive.

I had no trouble finding the house the knights had put at the disposal of Sultan Cem and where he had spent thirty-four days. But I could not get in. It is the best-preserved of the sandstone mansions lining the street that goes down to the port, just above the palace of the Great Master. It is not much different from the one next to it, which today houses the French consulate. I entered through the open door and found myself in a cool courtyard with a nice garden in the shade of palm trees. I pictured Sultan Cem in this same garden, hand-feeding one of the famed falcons of Rhodes. He must have looked anxious. Even though he was enjoying a moment of safety, his future was uncertain. He had left his family in Cairo for the love of the throne, and he was ready to negociate with his enemies. Did he consider himself a traitor, or was his claim to the throne, his hunger for power stronger than his scruples? We will never know. The novels written about him are mostly based on historical facts and barely try to unravel his state of mind. Before going up the stairs, I stayed in the shade of the garden for a moment, where the green blended gracefully with the stone. And I decided that one day, I would write about the adventures of Sultan Cem without regarding him as an exiled prince, but as an incarnation of the tensions the West is preoccupied with, although it refuses to admit – what we call today “the clash of civilizations” and of which the Great Turk is somewhat the symbol. As I walked out of the old town of stone houses, mosques and churches, magnificent fountains built by the Ottomans and narrow streets covered in the stone mosaics the Greeks call khokaklia, I seemed to hear a whisper. A voice was whispering to me that the sad story of Sultan Cem was just beginning and that it had to be traced back to the shores of France. And yet, what I took for the voice of the unfortunate son of the Conqueror was probably nothing but the wild wind of Rhodes.

Translated from French by Velina Minkoff